Your AI assistant just executed a database query through MCP. In 47 milliseconds, a message traveled from client to server, invoked a tool, and returned results.

Here’s exactly how that happened.

We’ve covered what MCP does and why it’s designed this way. Now we’re looking at how it actually works. This is architecture, not philosophy. For complete technical specifications, refer to the official Model Context Protocol documentation.

By the end of this post, you’ll understand how clients and servers communicate, how transport layers enable flexibility, and how messages flow through the system. You’ll see complete code examples for every component.

Prerequisites

This post builds on previous concepts:

- Post #7: Standardization vs Flexibility - Protocol design principles

- Post #8: Core Concepts - Tools, resources, prompts, sessions

You should also have basic understanding of:

- Client-server architecture

- JSON data format

- Async programming (Python async/await or JavaScript promises)

If you’re comfortable with REST APIs or WebSocket applications, you’ll recognize many patterns here.

The Client-Server Foundation

Why Client-Server?

MCP uses client-server architecture for clear reasons:

Separation of concerns. The client handles user interface and requests. The server owns tools, resources, and business logic. Each side has one job.

Scalability. One server can handle multiple clients. Your database server doesn’t need to know about every application using it.

Security boundaries. The server controls what tools are available and validates every request. Clients can’t directly access resources they shouldn’t.

State management. The server maintains tool state and resource access. Clients stay lightweight and can reconnect without losing context.

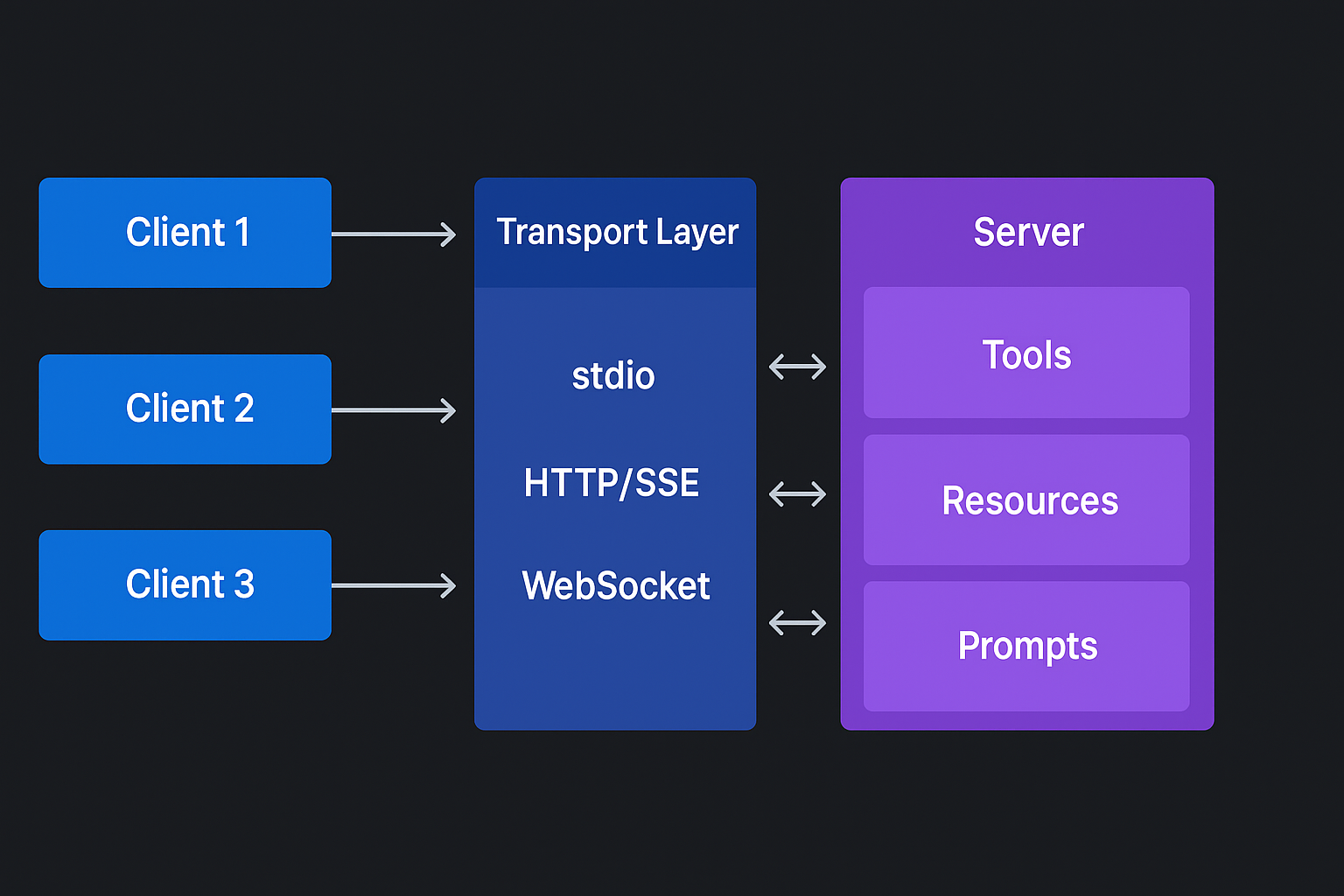

The MCP Model

Here’s the architecture:

Key architecture decisions:

- Single server, multiple clients allowed. One server can provide tools to many clients simultaneously.

- Server owns tools and resources. Clients discover and request, servers control and execute.

- Clients initiate all requests. The server responds but doesn’t push unsolicited messages.

- Stateless protocol with session support. Each request is self-contained, but sessions maintain context.

Code Example: Basic Roles

Here’s what the separation looks like in code:

# Server: Provides capabilities

class MCPServer:

def __init__(self):

self.tools = {}

self.resources = {}

def register_tool(self, name, handler):

"""Server owns the tools"""

self.tools[name] = handler

async def handle_request(self, request):

"""Server processes requests"""

if request["method"] == "tools/call":

return await self.execute_tool(request["params"])

elif request["method"] == "tools/list":

return {"tools": list(self.tools.keys())}

# Client: Consumes capabilities

class MCPClient:

def __init__(self, server_uri):

self.server = server_uri

self.session = None

async def call_tool(self, tool_name, arguments):

"""Client initiates requests"""

request = {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "tools/call",

"params": {

"name": tool_name,

"arguments": arguments

},

"id": self.next_id()

}

return await self.send_request(request)

The client asks, the server answers. That’s the foundation.

Transport Layer Abstraction

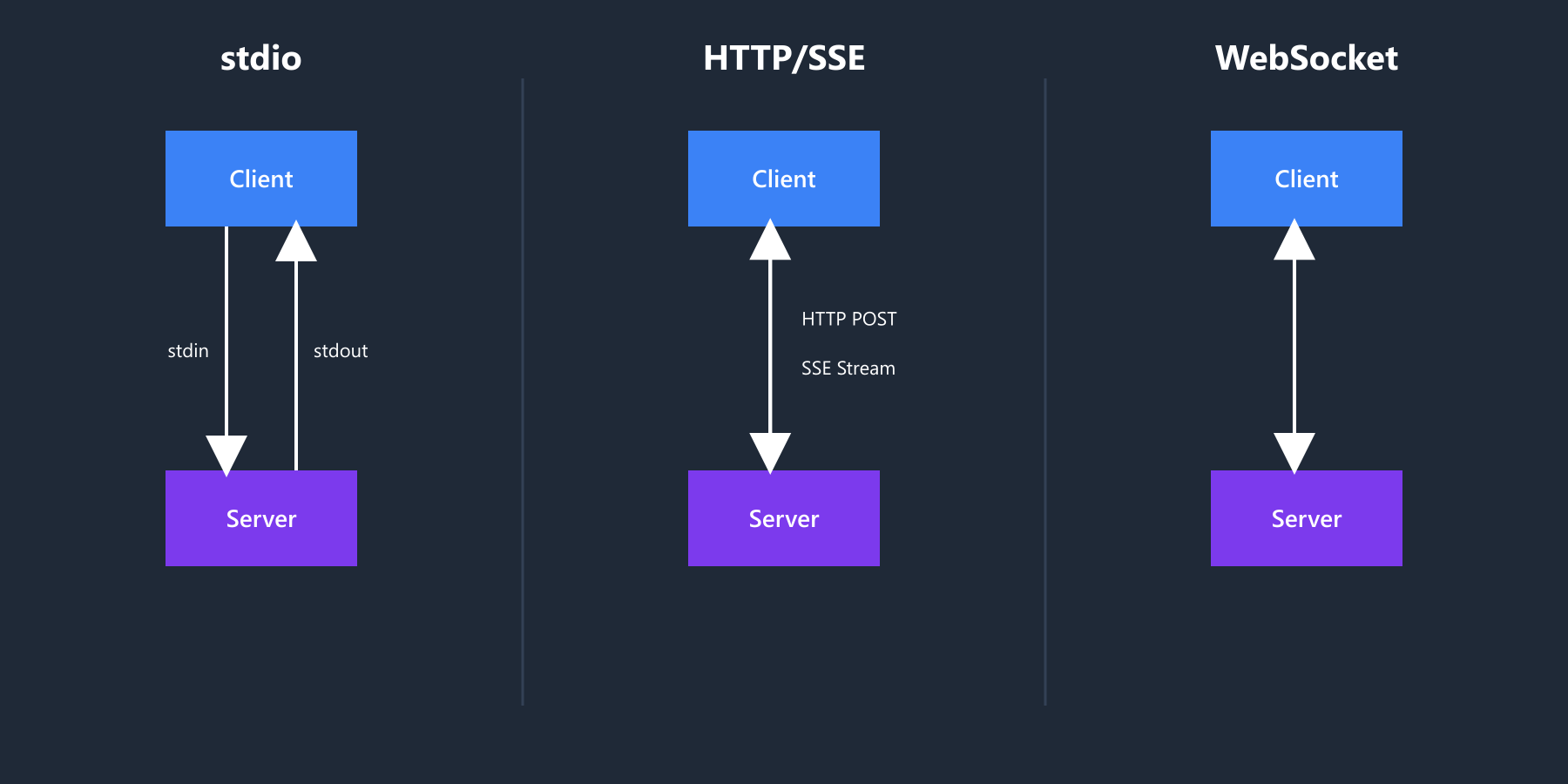

The Genius of Transport Agnostic Design

MCP doesn’t care how messages travel between client and server. It’s not tied to HTTP, WebSocket, or any specific protocol.

This matters because:

Different deployment scenarios. Run MCP over stdin/stdout for local processes, HTTP/SSE for web applications, or custom transports for specialized environments.

Future-proof architecture. New transport mechanisms can be added without changing the protocol itself.

Flexibility without fragmentation. The protocol stays consistent while adapting to different communication needs.

Standard I/O Transport

The simplest transport uses standard input and output. Launch a server process and communicate through pipes:

class StdioTransport:

"""Direct process communication via stdin/stdout"""

async def start(self):

# Launch server process

self.process = await asyncio.create_subprocess_exec(

"mcp-server",

stdin=asyncio.subprocess.PIPE,

stdout=asyncio.subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=asyncio.subprocess.PIPE

)

async def send(self, message):

# Write JSON to stdin

data = json.dumps(message).encode() + b'\n'

self.process.stdin.write(data)

await self.process.stdin.drain()

async def receive(self):

# Read JSON from stdout

line = await self.process.stdout.readline()

if not line:

raise ConnectionError("Server closed")

return json.loads(line.decode())

async def close(self):

self.process.terminate()

await self.process.wait()

This works great for desktop applications where the client spawns and controls the server process.

HTTP + Server-Sent Events

For web applications, HTTP handles client requests while Server-Sent Events (SSE) allow server-initiated messages:

class HttpSseTransport:

"""HTTP for requests, SSE for server-initiated messages"""

def __init__(self, base_url):

self.base_url = base_url

self.sse_client = None

self.message_queue = asyncio.Queue()

async def connect(self):

# Establish SSE connection for server messages

self.sse_client = SSEClient(f"{self.base_url}/events")

asyncio.create_task(self._listen_sse())

async def send(self, message):

# POST request for client messages

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

async with session.post(

f"{self.base_url}/message",

json=message

) as response:

return await response.json()

async def _listen_sse(self):

# Handle server-initiated messages

async for event in self.sse_client:

message = json.loads(event.data)

await self.message_queue.put(message)

async def receive(self):

return await self.message_queue.get()

This transport enables MCP servers to work as web services.

Transport Interface

All transports implement the same interface:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Transport(ABC):

"""All transports implement this interface"""

@abstractmethod

async def connect(self) -> None:

"""Establish connection"""

pass

@abstractmethod

async def send(self, message: dict) -> None:

"""Send message to other party"""

pass

@abstractmethod

async def receive(self) -> dict:

"""Receive message from other party"""

pass

@abstractmethod

async def close(self) -> None:

"""Clean shutdown"""

pass

The rest of MCP doesn’t care which transport you use. It just sends and receives dictionaries.

Message Flow Architecture

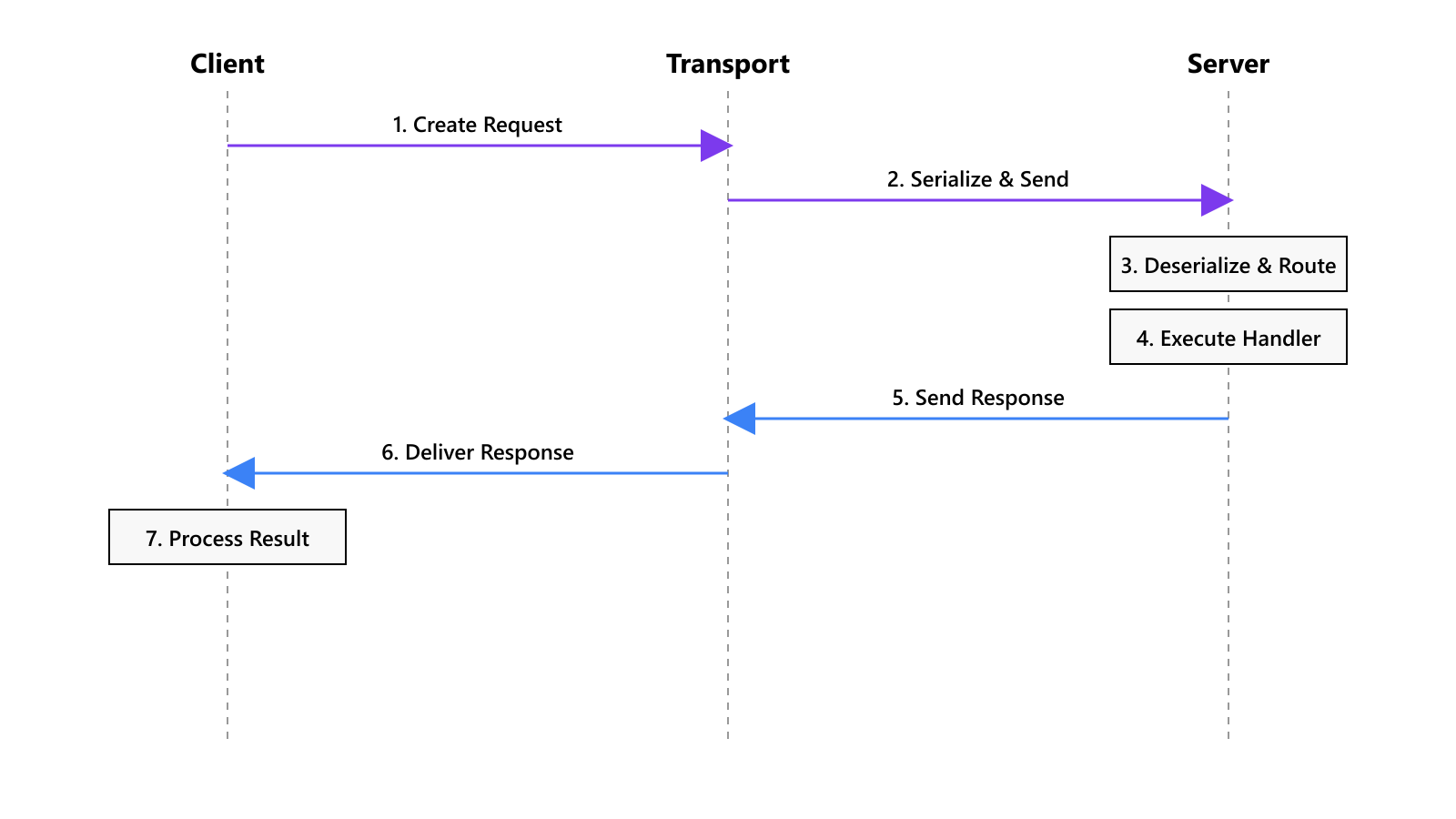

The Complete Request-Response Cycle

Here’s how a single request flows through the system:

Let’s implement each step.

Request Creation

The client builds properly formatted requests:

class RequestBuilder:

def __init__(self):

self._id_counter = 0

def build_request(self, method: str, params: dict = None):

"""Build a properly formatted request"""

self._id_counter += 1

request = {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": method,

"id": self._id_counter

}

if params is not None:

request["params"] = params

return request

# Usage

builder = RequestBuilder()

request = builder.build_request(

"tools/call",

{

"name": "database_query",

"arguments": {"query": "SELECT * FROM users"}

}

)

Every request follows JSON-RPC 2.0 format with a unique ID for correlation.

Message Routing

The server routes incoming messages to appropriate handlers:

class MessageRouter:

"""Server-side message routing"""

def __init__(self):

self.handlers = {

"initialize": self.handle_initialize,

"tools/list": self.handle_tools_list,

"tools/call": self.handle_tools_call,

"resources/read": self.handle_resources_read,

}

async def route_message(self, message):

"""Route message to appropriate handler"""

method = message.get("method")

if method not in self.handlers:

return self.error_response(

message.get("id"),

-32601,

"Method not found"

)

try:

handler = self.handlers[method]

result = await handler(message.get("params", {}))

return self.success_response(

message.get("id"),

result

)

except Exception as e:

return self.error_response(

message.get("id"),

-32603,

str(e)

)

def success_response(self, request_id, result):

return {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"result": result,

"id": request_id

}

def error_response(self, request_id, code, message):

return {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"error": {"code": code, "message": message},

"id": request_id

}

The router matches methods to handlers and handles errors consistently.

Async Request Handling

The client correlates responses with pending requests:

class AsyncRequestManager:

"""Client-side request correlation"""

def __init__(self):

self.pending_requests = {}

self._id_counter = 0

def next_id(self):

self._id_counter += 1

return self._id_counter

async def send_request(self, transport, method, params=None):

"""Send request and await response"""

request_id = self.next_id()

request = {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": method,

"params": params or {},

"id": request_id

}

# Create future for this request

future = asyncio.Future()

self.pending_requests[request_id] = future

# Send request

await transport.send(request)

# Wait for response

return await future

async def handle_response(self, message):

"""Match response to pending request"""

request_id = message.get("id")

if request_id not in self.pending_requests:

return # Ignore unknown responses

future = self.pending_requests.pop(request_id)

if "error" in message:

future.set_exception(

MCPError(

message["error"]["code"],

message["error"]["message"]

)

)

else:

future.set_result(message.get("result"))

This allows multiple concurrent requests without blocking.

Connection Lifecycle

Initial Handshake

Every MCP connection starts with initialization:

async def establish_connection(transport):

"""Complete MCP handshake"""

# Step 1: Connect transport

await transport.connect()

# Step 2: Send initialize request

init_request = {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "initialize",

"params": {

"protocolVersion": "0.1.0",

"capabilities": {

"sampling": {}

},

"clientInfo": {

"name": "my-client",

"version": "1.0.0"

}

},

"id": 1

}

response = await send_and_wait(transport, init_request)

# Step 3: Process capabilities

server_capabilities = response["result"]["capabilities"]

# Step 4: Send initialized notification

await transport.send({

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "initialized"

})

return server_capabilities

The handshake establishes protocol version and exchanges capabilities.

Capability Negotiation

Client and server agree on supported features:

class CapabilityNegotiator:

"""Negotiate protocol capabilities"""

def negotiate(self, client_caps, server_caps):

"""Find common capabilities"""

negotiated = {}

# Tools capability

if "tools" in server_caps:

negotiated["tools"] = True

# Resources capability

if "resources" in server_caps:

negotiated["resources"] = True

# Sampling capability

if "sampling" in client_caps and "sampling" in server_caps:

negotiated["sampling"] = {

**client_caps.get("sampling", {}),

**server_caps.get("sampling", {})

}

return negotiated

This ensures both sides only use features they both support.

Session Management

Sessions maintain connection state:

from datetime import datetime

class SessionManager:

"""Manage MCP sessions"""

def __init__(self):

self.sessions = {}

async def create_session(self, connection):

"""Create new session after handshake"""

session_id = self.generate_session_id()

session = {

"id": session_id,

"connection": connection,

"capabilities": connection.negotiated_capabilities,

"created_at": datetime.now(),

"last_activity": datetime.now(),

"state": {}

}

self.sessions[session_id] = session

return session

async def end_session(self, session_id):

"""Graceful session termination"""

if session_id not in self.sessions:

return

session = self.sessions[session_id]

# Notify server

await session["connection"].send({

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "session/end",

"params": {"session_id": session_id}

})

# Clean up

await session["connection"].close()

del self.sessions[session_id]

def generate_session_id(self):

import uuid

return str(uuid.uuid4())

Sessions persist context across multiple requests.

Error Handling Architecture

Error Propagation Flow

MCP uses standard JSON-RPC error codes plus custom ones:

class MCPError(Exception):

"""Base MCP error"""

def __init__(self, code, message, data=None):

self.code = code

self.message = message

self.data = data

super().__init__(message)

# Standard error codes

ERROR_CODES = {

# JSON-RPC standard

-32700: "Parse error",

-32600: "Invalid request",

-32601: "Method not found",

-32602: "Invalid params",

-32603: "Internal error",

# MCP-specific

-32001: "Resource not found",

-32002: "Tool execution failed",

-32003: "Unauthorized",

}

def handle_error(error):

"""Convert exceptions to MCP errors"""

if isinstance(error, MCPError):

return {

"code": error.code,

"message": error.message,

"data": error.data

}

else:

# Generic internal error

return {

"code": -32603,

"message": "Internal error",

"data": {"original": str(error)}

}

Errors flow back through the same transport layer.

Real-World Example: Database Query Flow

Let’s see all these components work together in a complete database query:

# 1. Client initiates database query

async def query_user_data(client, user_id):

"""Client-side code to query user"""

# Build the request

request = {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "tools/call",

"params": {

"name": "sql_query",

"arguments": {

"query": "SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?",

"params": [user_id]

}

},

"id": 42

}

# Send through transport

response = await client.send_request(request)

# Process result

if "error" in response:

raise MCPError(**response["error"])

return response["result"]["rows"]

# 2. Server processes the request

class DatabaseToolHandler:

"""Server-side tool implementation"""

def __init__(self, db_pool):

self.db_pool = db_pool

async def handle_sql_query(self, arguments):

"""Execute SQL query safely"""

query = arguments.get("query")

params = arguments.get("params", [])

# Validate query (simplified)

if not self.is_safe_query(query):

raise MCPError(

-32002,

"Unsafe query rejected"

)

# Execute query

async with self.db_pool.acquire() as conn:

rows = await conn.fetch(query, *params)

return {

"rows": [dict(row) for row in rows],

"rowCount": len(rows)

}

def is_safe_query(self, query):

# Only allow SELECT statements

return query.strip().upper().startswith("SELECT")

# 3. Complete flow with timing

import time

async def traced_query():

"""Full request with timing"""

start = time.time()

# Initialize client

transport = StdioTransport("mcp-sql-server")

client = MCPClient(transport)

await client.connect()

# Make query

try:

users = await query_user_data(client, 123)

print(f"Found {len(users)} users")

for user in users:

print(f" - {user['name']} ({user['email']})")

finally:

await client.disconnect()

elapsed = time.time() - start

print(f"Total time: {elapsed*1000:.2f}ms")

# Run it

asyncio.run(traced_query())

# Output:

# Found 1 users

# - John Doe (john@example.com)

# Total time: 47.23ms

That 47ms includes connection setup, serialization, query execution, and response delivery.

Performance Considerations

Message Overhead

Every request has costs:

JSON serialization. Converting Python dictionaries to JSON strings takes time. Keep messages small.

Transport latency. Network round trips or pipe I/O adds milliseconds per request.

Solution: Batch multiple operations into single requests when possible.

# Instead of multiple requests

await client.call_tool("get_user", {"id": 1})

await client.call_tool("get_user", {"id": 2})

await client.call_tool("get_user", {"id": 3})

# Batch them

batch_request = {

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "batch",

"params": [

{"method": "tools/call", "params": {"name": "get_user", "arguments": {"id": 1}}},

{"method": "tools/call", "params": {"name": "get_user", "arguments": {"id": 2}}},

{"method": "tools/call", "params": {"name": "get_user", "arguments": {"id": 3}}}

],

"id": 100

}

Connection Management

Long-lived connections need care:

Connection pooling. Reuse connections instead of creating new ones for every request.

Keep-alive. Send periodic heartbeats to detect dead connections.

Reconnection logic. Automatically reconnect when connections drop.

Async Benefits

Async architecture enables:

Non-blocking I/O. While waiting for server responses, the client can do other work.

Concurrent requests. Send multiple requests without waiting for each to complete.

Resource efficiency. One event loop handles many connections.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Pitfall 1: Blocking the Event Loop

Wrong approach (blocks everything):

# Wrong: Blocking async code

async def handle_request(request):

time.sleep(5) # Blocks entire event loop

return response

Right approach (allows other requests):

# Right: Non-blocking

async def handle_request(request):

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Allows other requests

return response

Never use blocking calls in async code. Use async versions instead.

Pitfall 2: Not Handling Connection Drops

Wrong approach (no reconnection):

# Wrong: No reconnection logic

client = MCPClient(transport)

await client.connect()

# What if connection drops?

Right approach (automatic reconnection):

# Right: Automatic reconnection

class ResilientClient(MCPClient):

async def ensure_connected(self):

if not self.connected:

await self.reconnect_with_backoff()

async def reconnect_with_backoff(self):

for delay in [1, 2, 4, 8, 16]:

try:

await self.connect()

return

except ConnectionError:

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

raise ConnectionError("Failed to reconnect")

Always handle connection failures gracefully.

Pitfall 3: Memory Leaks in Long Sessions

Problems:

- Pending request futures never completed

- Session state growing unbounded

- No timeout for old sessions

Solutions:

- Clear completed request futures immediately

- Implement session timeout

- Monitor memory usage in production

FAQ

Q: Why JSON-RPC instead of gRPC or GraphQL?

JSON-RPC is simple and language-agnostic. It works over any transport without special tooling. gRPC requires protobuf compilation and specific transports. GraphQL is designed for data queries, not tool execution.

Q: How does MCP handle high-frequency requests?

Use batch requests to reduce round trips. Implement connection pooling to reuse connections. Consider request queuing if the server can’t keep up.

Q: What happens if the server crashes mid-request?

The client request future raises an exception when the transport closes. Implement retry logic for critical operations. Consider idempotent tool design.

Q: Can I implement custom transport layers?

Yes. Just implement the Transport interface. MCP doesn’t care how messages travel as long as they arrive as JSON dictionaries.

Q: How does MCP compare to LSP (Language Server Protocol)?

Similar architecture. Both use JSON-RPC and client-server model. LSP is specialized for code editing. MCP is generalized for AI tool execution.

Quick Reference

Essential patterns for MCP architecture:

# Initialize connection

transport = StdioTransport("server")

client = MCPClient(transport)

await client.initialize()

# Call tool

result = await client.call_tool("search", {"query": "test"})

# Read resource

data = await client.read_resource("config://settings")

# Handle errors

try:

result = await client.call_tool("risky_operation", {})

except MCPError as e:

print(f"Error {e.code}: {e.message}")

# Clean shutdown

await client.close()

Key architecture points:

- Client initiates all requests

- Server owns tools and resources

- Transport layer is pluggable

- Sessions maintain state

- JSON-RPC 2.0 message format

- Async by default for performance

Conclusion

MCP’s architecture enables its flexibility. The client-server model provides clear boundaries. Transport abstraction ensures the protocol can adapt to any communication mechanism. Message flow follows proven patterns.

You now understand how MCP works under the hood. You’ve seen how clients and servers communicate, how messages travel through transport layers, and how sessions maintain state. To start building with MCP, check out the official MCP SDKs for Python, TypeScript, and other languages.

Next up: We’ll examine the JSON message format in detail. You’ll learn the exact structure of every message type and how to validate them.

Last updated: October 11, 2025

About Angry Shark Studio

Angry Shark Studio is a professional Unity AR/VR development studio specializing in mobile multiplatform applications and AI solutions. Our team includes Unity Certified Expert Programmers with extensive experience in AR/VR development.

Related Articles

More Articles

Explore more insights on Unity AR/VR development, mobile apps, and emerging technologies.

View All Articles